Mythical Winged Creatures: A brief history of their symbolism in art and mythology

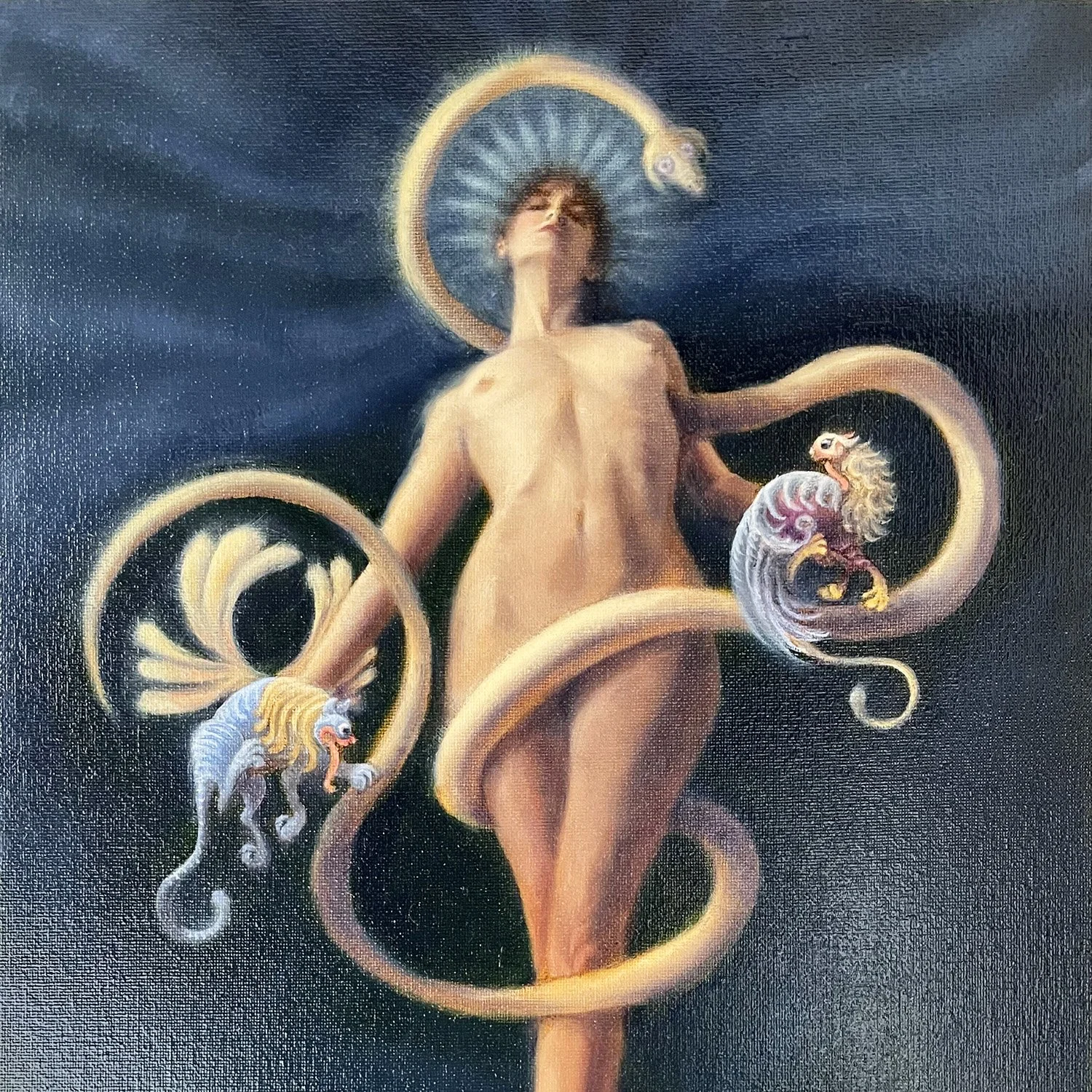

Detail from ‘Falling Angel’ by Karina Tarin

Why are we so obsessed with wings?

We humans have a long-standing love affair with wings, but where does it come from? In some ways the answer is obvious. After all, who hasn’t gazed up at the birds in the sky and wondered what it would feel like to fly? But our enthusiasm appears to stray far beyond personal dreams of flight, stumbling stubbornly into obsession territory. In fact it seems we’re keen to put wings on anything and everything: humans, horses, elephants, reptiles, lions… especially lions. Look back through the history of art and mythology and you’ll see we’ve been at it for millennia. It appears there’s a powerful force at play, driving humans to imagine and depict mythical winged creatures, again and again, apparently since the dawn of time. But what’s at the root of this obsession?

Because I, too, love a winged creature, I spent a rainy day researching their journey through mythology and art, their symbolic meaning, and why we need them in our world. It appears the story starts with a griffin…

The Griffin: the birth of an apex protector

The earliest physical evidence of a winged mythical beast is a griffin-like creature on a cylinder seal, made 5,000-6,000 years ago and unearthed in ancient Susa (now in Iran). At the time this seal was made, this was already a creature important enough to be chosen as a wealthy man’s symbol. At the same time, Ancient Egyptians were also ‘discovering’ griffins, evidenced by the comb-winged griffin adorning the fantastical Two Dog Palette - a ritual object made to be buried with kings (3,300-3,100 BC, now in the Ashmolean, Oxford). Was there cross-fertilisation of griffin mythology and inconography between these civilizations, or did they each imagine this hybrid beast independently?

Image 1: Griffin Cylinder seal Uruk period 4th millennium BC

Image 2: Griffin on Two Dogs Palette, Egyptian, 3300-3100 BC

The griffin gathered pace across the Ancient Near East, adorning burial objects, palace gates, temple walls and tombs. Its placement at the threshold of divine places and other worlds suggests its role as guardian and divine protector. And you can see how the griffin is designed perfectly for this job. With the head and wings of an eagle, and the body of a lion, the griffin is a deadly mix of two apex predators: the king of the beasts, and the king of the skies. You can almost hear the conversation that launched the griffin… ‘so, imagine if the lion could fly, and also had the vision of an eagle… then nothing would get past it!’.

To put this in context, we must understand that protectors were necessary, even for kings. The fear of supernatural forces was real: how else to explain the storms, pestilence, or enemies that could appear suddenly and lay waste to your realm? We can see how a terrestrial lion would be an excellent defender, but not quite sufficient to tackle such an enemy. A divine guardian needed far-seeing eyes and dominion of the heavens as well. Hence the timely birth of the griffin, the perfect apex protector.

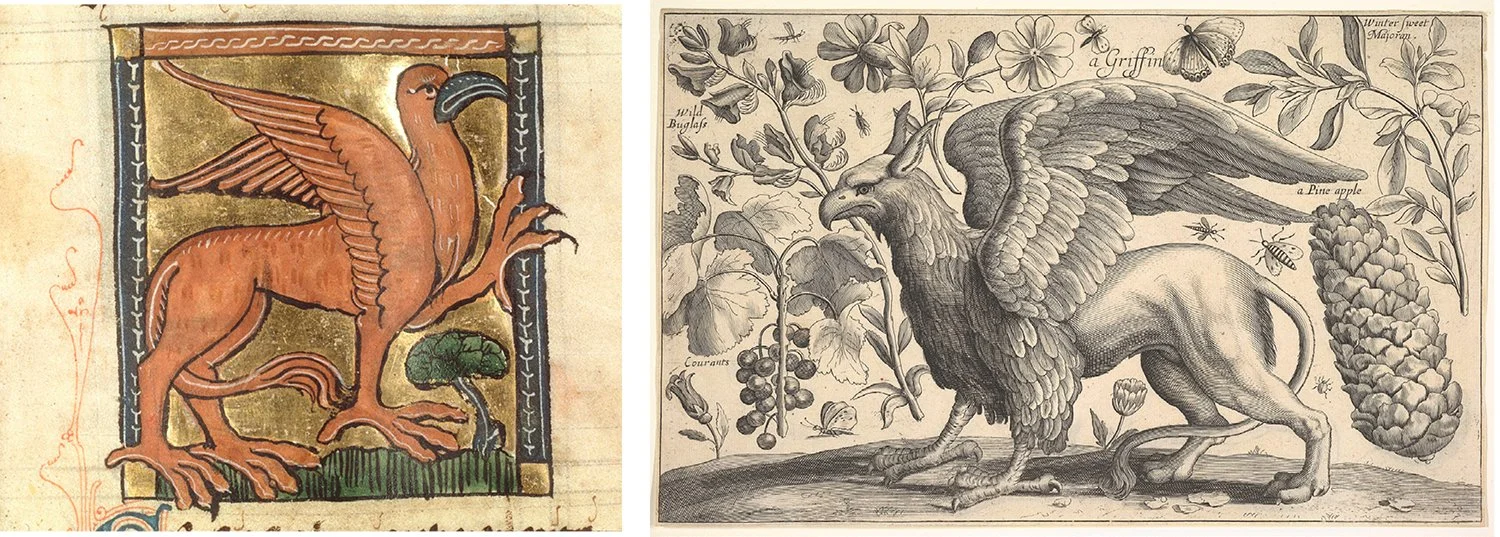

Griffin symbolism endured from its origin in the Ancient Near East, gathering momentum through the mythology of Ancient Greece and the Scythian plains of Central Asia, and tumbling elegantly across the medieval world to land firmly in Christian iconography (with a day job as a popular heraldic device). Always symbolic of strength, guardianship and divine power, it has been employed as stalwart protector and companion of royalty, religions, and the powerful to this day.

Image 1: Griffin from ‘Der Naturen Bloeme’, an early Dutch illuminated manuscript (c. 1340-1350) | Image 2: Griffin etching, 1625–77

(Interestingly the griffin came to symbolise the Catholic church’s views on the sanctity of marriage, as it was said that the griffin mated for life, and wouldn’t seek a new mate even if their partner died.)

More Winged Lions: kings of the skies

If there are nefarious and unexplained forces stacked against you (which there always are in the ancient world), it’s good to have a lion on your side. Add wings, and they’re even better protectors, fielding attacks from airborne demons and spirits too.

The Assyrians thought so too. Enter the Lamassu around 950 BC, a celestial being from ancient Mesopotamian religion, with a human head (for wisdom), a lion’s (or bull’s) body, and the wings of an eagle. Like griffins, Lamassu were protectors, placed at entranceways to guard against evil. They started life as household spirits of the common Assyrian people, later becoming associated with royal protection. To protect common houses, the Lamassu were engraved onto clay tablets, which were then buried under the door’s threshold. Later, huge, imposing statues stood sentinel at city, palace, and temple entrances to give an overwhelming impression of power and serve as a reminder of divine protection and the divine right of kings.

One of my favourite things about Lamassu is their five legs. If you look at them from the side, they are walking, but viewed from straight on, they stand to attention. If you see them from an oblique angle, you can see all five legs (see image below). If you want to visit one in person, the British Museum has six Lamassus in residence. Lamassu appeared frequently in art across the Mesopotamian region until around 600 BC.

Lamassu, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Assyrian, c. 883–859 BC

Winged lions have continued as a favoured symbol of power and protection in art and mythology across the world since the first griffin flapped its wings over 5000 years ago. Below I’ve included some of the other notable examples of mythical winged lions from the last 4500 years (in roughly chronological order):

The Sphinx: In Ancient Greek myth, the Sphinx (like Lamassu) has the head of a human, the body of a lion, and the wings of an eagle. The Greek sphinx is female, treacherous and merciless, killing and eating all who fail to solve her riddle. In contrast, Egyptian sphinxes are typically male, and a benevolent representation of strength and ferocity (hmm, I wonder who was writing these myths…), typically without wings. Interestingly, both Greek and Egyptian sphinxes were regarded as guardians, with their statues yet again guarding temples. During the Renaissance, the sphinx enjoyed a major revival in art, where its physical characteristics and temperament continued to vary, depending on the artist.

Sphinx: An original oil painting by Karina Tarin (a re-imagining of the original Greek mythical creature)

Flying Lion: In Ancient India, ‘flying-lion’ are mentioned in the Ramayana, a Sanskrit epic (from ≈ 600 BC).

Achaemenid Winged Lion: The winged lion was a favourite motif in Achaemenid art (Persia, now Iran, 550-330 BC), and was a symbol of the power of the Achaemenid dynasty. The Golden Lion Rhyton is one of the most spectacular surviving examples.

Achaemenid gold rhyton in the shape of a winged lion, c. 550-330 BC (image taken by Following Hadrian)

Pixiu: Since the Han Dynasty in China (206 BC – 220 AD) winged-lion protectors called Pixiu have patrolled the heavens to guard their masters from demons and evil spirits, even beyond the grave. Their sharp teeth would drain the essence of the demon, converting it to wealth. After death, the Pixiu would help their masters ascend to heaven by flying them there on their backs. Like the griffins and Lamassu before them, the Pixiu were used as tomb guardians for emperors and royalty.

One of the two Pixiu statues from the Yongning Tomb of the Emperor Wen of the Chen Dynasty. Qixia District, Nanjing. (A single photo is mirrored here) Photo by Shallowell

St. Mark the Evangelist: The winged lion became the symbol of St Mark the Evangelist from around 400 AD, featuring heavily in medieval Christian illuminated manuscripts, like the gorgeously illustrated Book of Kells – one of all time my favourites.

Christian symbol of resurrection: In Christian iconography, lions (often winged in the Book of Kells) were also symbolic of resurrection, as it was thought lion cubs were born dead, but awakened by their father’s breath after three days.

Detail of Resurrection, an oil painting by Karina Tarin, with winged lions, inspired by medieval Christian iconography

The Lion of Venice: The winged lion became the official emblem of the Republic of Venice in the 9th century, when the remains of St Mark the Evangelist were taken from Alexandria and transported to Venice to be re-buried in the Basilica of St. Mark. The Lion of Venice represents power, majesty, and divine protection over the city.

Vittore Carpaccio, 1516. The Lion of St Mark (detail) Tempera on canvas, Palazzo Ducale, Venice

Other Hardcore Winged Beasts as Guardians

Once we got started, it seems we couldn’t break the habit of giving hardcore beasts wings so they could become extra good protectors. We needed them to do what we couldn’t, trusting them to protect us from intangible but ubiquitous threats from evil spirits of the skies and vaporous mists. Here are a few that we kept in our back pocket in case the winged lions were busy that day…

Gorgons: Gorgons were a favourite subject in ancient Greek, Roman and Etruscan art. It’s thought their origin may have been inspired by the demonic, lion-headed Mesopotamian deity, Lamashtu (also winged). The earliest mentions appear in works by Homer and Hesiod (c. 700-600 BC), and later develop into the three gorgon sisters of the Perseus-Medusa story. The Greek mythographer Apollodorus gives the most detailed description: ‘... the Gorgons had heads twined about with the scales of dragons, and great tusks like swine's, and brazen hands, and golden wings, by which they flew’. Despite their commonly hideous appearance, Gorgons and Gorgoneia were believed to have a protective function, and were depicted on temple pediments such as the Gorgon Pediment from the Temple of Artemis, Corfu (6th century BC). Originally hideous monsters, by the 5th century BC, Pindar describes his snake-haired Medusa as ‘beautiful’. This is echoed by the Roman poet Ovid who describes her as a ‘beautiful maiden’ (although he thinks her no longer beautiful after her hair was transformed into snakes by a wrathful Athena [Minerva in the Roman stories]).

Detail from And the Snakes Were Her Friends: Original oil painting of Medusa by Karina Tarin

Gargoyles: Gargoyles are typically fantastical, winged creatures, thought to have an apotropaic (protective) function. It is said that two gargoyles stand guard at the gateway of the city of Amiens, France, and anyone who has bad intentions towards the city or its people would be showered with acid spit before being allowed to enter. Conversely, the king of Amiens would be showered with coins with every return.

Dragons: Winged reptiles? Of course - bring it on. There’s been a lot written about dragons, so I won’t say too much here, except that while western dragons are bad-tempered, mostly protecting their own treasure, Chinese dragons are thought to be benevolent creatures, protecting their people, and bringing good fortune. The dragon is one of the most enduring winged creatures in the modern arts, with prominent placement in books and films, including the popular How to Train your Dragon and Harry Potter.

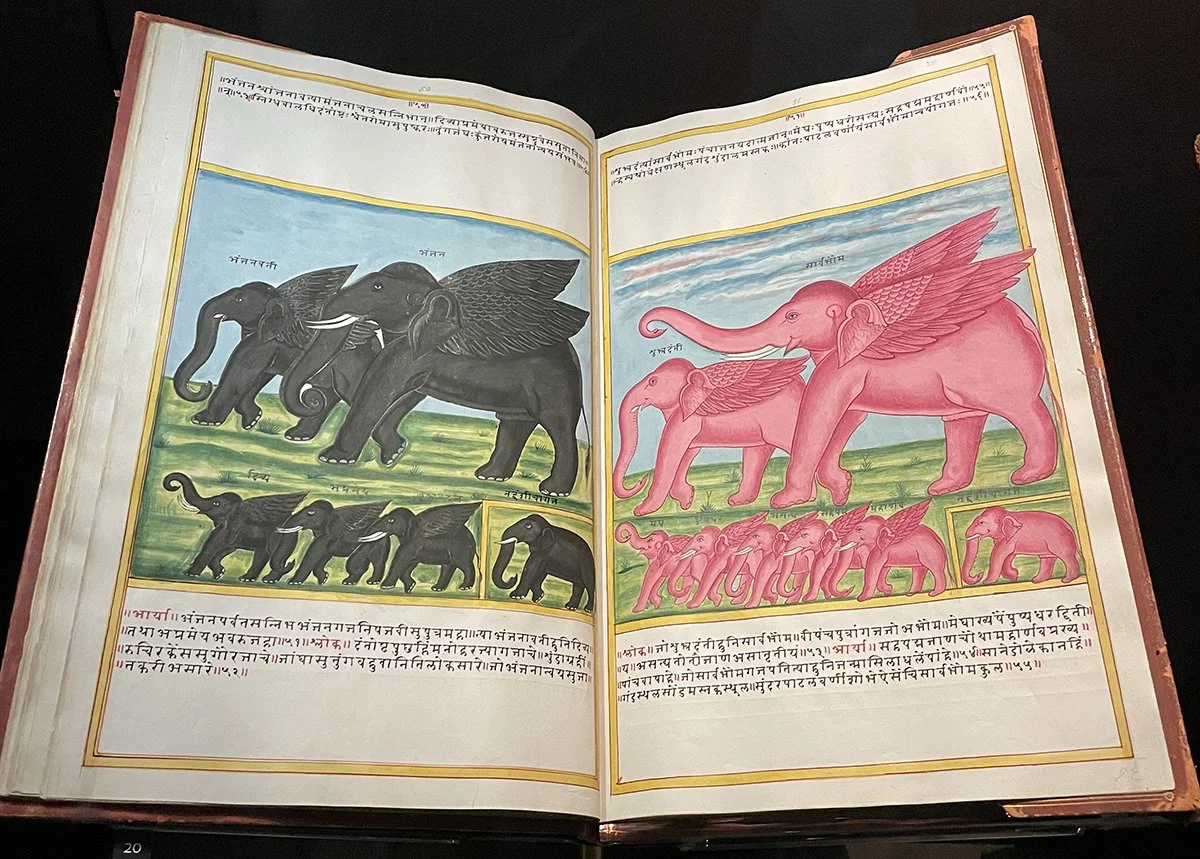

Winged elephants: According to Hindu tradition, Brahma created eight winged elephants to guard the compass points. Terrestrial elephants also once had wings, but they were stripped as punishment for unruly behaviour. I love the idea that our massive, majestic but undeniably earth-bound elephants could once have soared gracefully over our heads.

Winged Elephants: As seen at the ‘Treasured’ exhibition at the Weston Library, Oxford Elephantology, India, c. 1874 - 1878

Egyptian Deities: Power and protection, the shelter of wings

We gave strong beasts the power of flight to guard us from terrestrial and aerial threats, patrolling the skies where we couldn’t. The Ancient Egyptians understood the importance of this, and gave their protective gods and goddesses wings too.

Ancient Egypt had many winged deities, including Ra, Horus, Isis, Nephthys, Ma’at and Nut. All played a protective role of some form: over the sun and crops (Ra), the skies (Nut and Horus), the dead (Nephthys), the natural world (Isis), order (Ma’at) and kings (both Ra and Horus). While these gods and goddesses took an actively protective role, exemplified by Ra’s nightly battles with chaotic forces, there was also something more physically sheltering about their wing iconography. Their guardianship was visually represented by their wide, outstretched wings, often forming a huge, canopy over the people and events below them. The visuals are so powerful that we can almost feel the shade of the huge wings above us.

Their wings were such a compelling emblem that they became a visual shortcut to represent divine power and protection. In this way, Ra and Horus came to be symbolically represented by a winged sun-disc. Because Ra and Horus were protectors of the king, and because the pharaohs also considered themselves the earthly incarnation of these gods, the winged sun-disc became, by extension, a symbol of divine kingship across the Near East. The power and protection cascaded: the gods protected the king, and the king protected his people.

Knowing how birds tuck their young beneath their wings, it’s easy to see how wings became a compelling symbol of protection. At a time when common people had so little security, we can see the appeal of being sheltered by a huge pair of strong wings.

Winged sun disc on an Ancient Egyptian coffin in the Vatican Museums. The outstretched wings shelter those beneath.

Divine Intervention: Bridging the gap between heaven and earth

With the Egyptian deities and their earthly incarnations, we have started to bridge the gap between heaven and earth. That in-between space, that realm of air, was an untouchable place for the ancients, governed by the winds, traversed only by divine messengers and winged deities (…um, and birds, and all the winged beasts they just created, and the demons and evil spirits of course…but that all makes it sound less poetic and a lot more crowded…). So let’s start with the bringers of the winds, and end with the angels.

Winged deities who were ‘bringers of’…

The Anemoi. The Anemoi, Greek gods of the four winds, brought the seasons, and were first mentioned in Hesiod’s Theogony around 730–700 BC. They were personified as winged men, or sometimes winged horses (of ‘breathtaking majesty’, according to Plato). They are the offspring of Eos, goddess of dawn, and her husband Astreus, god of dusk. They were minor gods, subject to Aeolus, ruler of the winds. Each is linked with a point of the compass and their own season:

Boreas is the North Wind, and bringer of winter cold air

Zephyrus is the West Wind, bringer of spring and early summer breezes

Notus is the South Wind, and bringer of the hot summer winds, and the storms of later summer and autumn

Eurus is the East Wind, associated with Autumn

Winged Greek god of the north wind, Boreas. Detail from an Apulian red-figure oenochoe, c. 360 BC.

As messengers of nature, the winds were given wings to allow them to travel swiftly across the world to bring the winds and the seasons. In fact, this seems to be a general rule for applying wings to personifications in Ancient Greek, Roman and Christian lore - that wings were either for messengers (who needed to travel swiftly to deliver their messages), or deities who were ‘bringers of’ something (who therefore needed to travel around to deliver).

Let’s look, then at the other Greek deities who were ‘bringers of’ (they all had Roman counterparts, but I’ll focus on the original Greek here…):

Bringer of love: Eros, was originally a primordial god, and later became the son of Aphrodite. He is god of love (which can also arrive swiftly), traditionally depicted as a winged infant or youth carrying his bow and arrow.

Bringer of victory: Nike, goddess of victory, was often depicted with wings outstretched as she hovers over the victors. While wars are often long, victory arrives swiftly. Perhaps her wings also suggest the freedom that comes with victory?

Bringer of retribution: Nemesis was the goddess of divine retribution. Her wings signify that justice can catch up with us at any time, anywhere…

Bringer of death: Thanatos, winged god of death, is a minor deity, especially related to the bringing of a peaceful end (rather than being ruler of the underworld). He is twin brother of Hypnos (sleep), and son of Nyx (night) and Erebos (darkness).

Bringer of sleep: Hypnos was god of sleep, twin brother of Thanatos (above). Sometimes he was shown with wings sprouting from his back like his brother, but sometimes his wings sprung from his temples (to signify the flight of our dreams?), as seen on the bronze head from a statue of Hypnos (350-200 BC), now housed in the British Museum.

Bronze Head of Hypnos found in Civitella d'Arno, Italy 350-200BC. Now in the British Museum, room 22. Photo by Paul Hudson via Wikipedia Commons.

Bringer of dawn: Eos, the ‘rosy fingered’ goddess of dawn is often depicted with wings. She rose each morning from her home at the edges of Oceanus to chase away the night and bring us light.

Bringer of… the soul? – Psyche. OK, so Psyche, goddess of the soul, doesn’t fit with my ‘bringer of’ theory. Psyche was gifted butterfly wings when she was granted immortality. Perhaps these were to help her ascend to Mount Olympus? Or maybe the butterfly wings signify the ethereal nature of the soul: try to grasp it, and the concept turns to glittering dust in our hands.

Winged messengers from Greek mythology

Some Greek deities were also messengers, doubling their need for wings. For example:

Hermes: God, messenger and Psychopomp. Hermes was the personal messenger of Zeus, general messenger for the gods, and also a psychopomp, or ‘soul guide’, who led the deceased to the underworld. Because of these multiple roles, Hermes could easily travel between heaven, earth and the underworld, aided by his winged sandals, often delivering messages to humans on earth.

Iris: Messenger and goddess of the rainbow. Just as Hermes was personal messenger for Zeus, Iris was personal messenger and handmaiden of Hera (Zeus’ wife). Like Hermes, she also carried messages for the other deities too, said to travel on her rainbow. Despite her handy rainbow-vehicle, she was also depicted with wings.

Pegasus: Thunderbolt-bearer for Zeus. Pegasus was a winged horse born from the blood of Medusa’s neck when Perseus decapitated her. His sire was Poseidon, in his role as horse-god. Pegasus wasn’t strictly a messenger, instead acting as a kind of porter for Zeus, carrying his thunderbolts. I couldn’t leave him out though – a flying horse is far too good to be left on the shelf.

Bellerophon riding Pegasus and killing the Chimera, Roman mosaic, the Rolin Museum in Autun, France, 2nd to 3rd century AD

Angels: Winged messengers of Christianity

Just as Hermes and Isis carried messages from Greek gods to humans, angels became the intermediaries between heaven and earth in Christianity.

Interestingly, angels didn’t always have wings. In the bible, there is no mention of winged angels. It’s easy to get confused though, because winged Seraphim are described in the bible (six wings each; role – to constantly surround and worship God) and winged Cherubim (four wings each: role – guardians of sacred spaces), but these are a long way above angels in the order of things. In fact, Seraphim and Cherubim are the two highest orders of celestial beings (out of nine). To put this in context, archangels are number eight, and angels are the lowliest, at number nine. The role of angels is quite specific, and never overlaps with the duties of the Seraphim or Cherubim. Angels are divine messengers, protectors and ministers to humanity. Which is why they are so lowly. Understandably, looking after us unruly humans is just not such as great job as hanging out with God.

So…angels had no wings. Instead, in the bible, angels use a ladder or staircase to move between heaven and earth, just as humans would. There’s only one problem with this as far as artists were concerned: it just isn’t a great look. As an artist, I have never, ever, been tempted to paint a ladder. Wings on the other hand present a whole world of opportunities. So artists gave angels wings. Well, that’s how I imagine it at least, but I think perhaps it was a little more involved than that…

Here’s what likely happened in a nutshell (based on actual history, rather than my whim): Ancient Greece had winged gods, goddesses and messengers. By 146 BC, the Romans had completely conquered the Greek city-states. The Romans adopted many of the Greek deities, but gave them new names. So, Zeus became Jupiter; Hera became Juno; Poseidon became Neptune, and so on. As such, the Romans were well versed with the iconography of winged Greek (and therefore Roman) deities and divine messengers, and continued this theme. Christianity was adopted as the official religion of the Roman Empire by Emperor Theodosius I in 380 AD. Roman artists were used to depicting divine messengers with wings, so did the same with Christian angels. In fact, the earliest known representation of angels with wings is on the Sarcophagus of Sarigüzel, near Istanbul, from exactly that time period: the reign of Theodosius I. So, now angels have wings.

Since then, winged angels have been a popular subject in Byzantine and European paintings and sculpture (NB: the Byzantine Empire was the continuation of the Roman Empire in its eastern provinces, centred around Constantinople). In Byzantine art, they were regularly depicted in mosaics and icon paintings. European medieval art borrows from the Byzantine tradition, and they became regular residents of medieval illuminated manuscript. Early Renaissance painters like Fra. Angelico and Jan van Eyck painted their angels with glorious, multicoloured wings (angels in Islamic Art also have multicoloured wings!). Art’s obsession with angels continued to gather pace through the Renaissance period, with angels appearing regularly in religious paintings, frescoes, and altarpieces. In Victorian times, angels were re-awoken by the Pre-Raphaelites, and came to embody a new ideal of beauty. With Jane Morris as their muse, the Pre-Raphaelites created a prototype for the Victorian angel which was somewhat more androgynous.

Detail from ‘Falling Angel’, an original oil painting by Karina Tarin

The symbolism of winged beings persists…

Winged creatures, beasts and beings are still popular in art and stories today, for adults as much as children (think of the runaway success of the ‘A Court of Thorns and Roses’ series). There’s a beauty, escapism, and freedom evoked by a pair of wings that we still need in our earthbound lives. Yet the more ancient symbolism of winged beings still exists… the divine guardian of entranceways; the sheltering protector with outstretched wings; and the celestial being that bridges the gap between heaven and earth. If you’re not convinced, drive up the A1 and feast your eyes on Antony Gormley’s magnificent Angel of the North.

The Angel of the North guards the entrance to the North of England, with outstretched, protective wings, reminiscent of Ancient Egyptian deities. Created by Antony Gormley

This blog was written by British contemporary artist Karina Tarin, whose work is inspired by ancient stories, symbolism, Renaissance and medieval art.